Matthew Kronsberg dishes on what rockers like Rod Stewart, Paul McCartney, and the Rolling Stones and their crews eat while on the road—and the lengths to which they’ll go to get a taste of home

Ask anyone who has ever gone on tour with a band about life on the road. Ask them about the sex and the drugs and the rock ‘n’ roll. Go ahead. After they stop laughing, you will probably hear stories of great adventures, discoveries, and camaraderie. Dig deeper, though, and the stories turn darker. The chronic sense of dislocation. The sleep deprivation. The Domino’s.

Not surprisingly, waking up in a tour bus outside an arena in a city you don’t recognize is not made any easier by weak coffee with a stale doughnut chaser. This is the moment where the glamour and romance of the touring life starts to crack. Because before the houselights dim and the crowd screams, before “Hello, Cleveland!” and the guitar solo, there is breakfast.

In the absence of sleep—and on tour, sleep will assuredly be absent—good food is often the crew’s (and the artists’) most reliable tether to comfort, health, and happiness. The headliner can significantly influence the food served to the crew, which can have a palpable effect on the morale of the tour.

When Rod Stewart played the Miami Arena in fall 1993, catering was housed in a windowless room, deep in the bowels of the since demolished stadium. Gray linoleum floors, gray Formica tables, fluorescent lights embedded in a yellowing drop ceiling. It was the kind of break room millions of workers know intimately—a pitiless bunker.

The breakfast spread was typical for an international arena tour: an assortment of breads, jams, eggs, and meat. Lots of coffee. PG Tips tea for the English among the crew, Barry’s for the Irish, Vegemite for the masochists.

One morning, eyes widened and steps quickened as the team neared the steam table. Heaped next to the bangers and eggs was kedgeree. Flaked fish (salt cod, in this case, but commonly made with anything from salmon to finnan haddie) mixed with rice and chopped hard-boiled eggs, seasoned with curry powder. The English say kedgeree came from the Raj, based on the Indian dish kitcheri, a mash of rice and lentils, traditionally eaten at breakfast. The Scottish say that it originated in Scotland, only picking up the curry while in the Subcontinent. This being a Rod Stewart tour, the Scottish-origin story prevails.

For the crew, most of whom hailed from the British Isles, the kedgeree provided a comforting connection to homes and families that they had been away from for months, and might not see for months to come. This is hearty breakfast stuff, made for people who may well miss lunch, engrossed in the intensely technical and physical demands of setting up a concert. It is also an assertion of Stewart’s heritage and identity that reaches far beyond kicking soccer balls into the crowd each evening.

The influence of an artist on a tour’s food does not always guarantee salutary effects on morale, however.

Paul McCartney famously runs a strictly meat-free tour. Potential crew members know about this, and must commit to a vegetarian diet before signing on. Paul’s tour, Paul’s rules. Don’t like it? Maybe Metallica’s hiring.

Aside from coming home healthier than they left, McCartney’s crew is known for getting some of the best vegetarian cooking anywhere. On any given night, dinner might include celeriac, chestnut, and pesto soup; sweet potato gnocchi with spinach-and–blue cheese sauce; a meatless Irish stew in puff pastry with colcannon; and no shortage of desserts. However good the catering, though—and however righteous the cause—the shift to tofu and tempeh can still be jarring for the average carnivorous crew member. Pockets of rebellion are all but inevitable.

Over the years, some crew have risked (and, according to a 2007 Waco Tribune-Herald column by rocker Ted Nugent, lost) coveted positions on such a high-profile tour as this for the sake of contraband meat. They forgot the first rule of the Hamburger Club: You don’t talk about the Hamburger Club. In cases like this, diet trumps all else—jobs, reputations, and morale are risked for food.

Sometimes though, the food on the plate is secondary. The act of taking a meal together, far from home, can be enough to stave off misery and desperation.

Thanksgiving 1989 found the Ramones playing the Biskuithalle in Bonn, Germany. The capital of West Germany at the time, Bonn was, as John Le Carré called it, “a Balkan city, stained and secret, drawn over with tramwire.” Without the illicit wonders of Hamburg, or the Cold War frisson of Berlin, Bonn provided few distractions for a punk band far from home. After a decade and a half with the group, tour manager Monte A. Melnick knew his charges well. It was at just these times—in the places in between, when everyone would rather be home—that TVs might find their way into hotel pools, and apologies and restitution risked becoming part of hotel checkout.

Melnick made a valiant attempt to arrange a traditional Thanksgiving dinner for the band and crew. “It could be hard explaining to a caterer in Europe what Thanksgiving was all about. In Germany, they didn’t really get it, but they tried.” The menu was a disappointment, to be sure, but with a decade and a half of hard touring behind them, the Ramones and crew were no strangers to Thanksgivings on the road. As it was, comfort was almost anathema to the band’s ethic; long after they could afford to travel by luxury coach, they stuck to the van. The Ramones were always about the wanting and not the having—still, what mattered was the effort to satisfy those wants. That attempt to ensure the gang’s welfare and happiness with a decent holiday dinner reinforced a bond that lasted through the group’s entire career.

Five years later, the Rolling Stones brought their Voodoo Lounge tour to Joe Robbie Stadium in Miami. This wasn’t your typical Stones concert (if there even is such a thing). This was going to be broadcast, and the addition of film crews and guest performers complicated what was a practiced, though still mammoth, operation. An extra day for rehearsals was added to the schedule, and that day, too, happened to be Thanksgiving.

Some of the crew had flown their families to Florida for the holiday. For the Americans on the tour, it was the closest they could come to being home. Just as Rod Stewart’s kedgeree provided a taste of home to the English, the turkey and stuffing, green beans, and pumpkin pie would give the Stones’ American contingent the fuel to soldier on for months to come. Tour management wanted there to be a proper Thanksgiving dinner. It would be a time for the tour to come together as a community.

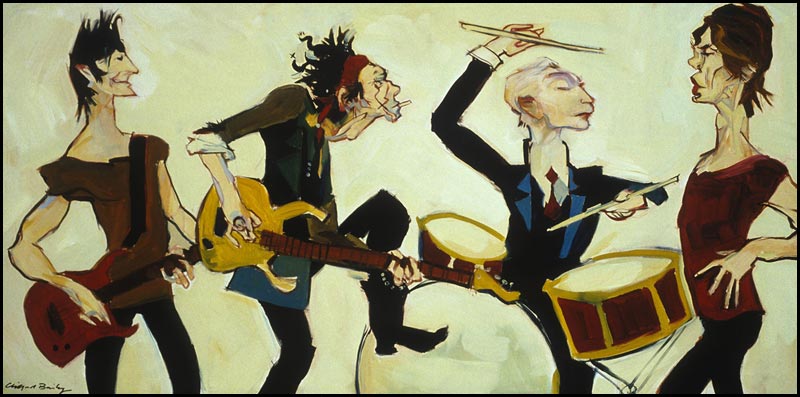

The band would be there. Bo Diddley would be there. Keith’s mum would be there. And the roughly 300 crew working that Thursday would be there. The Stones marshaled resources unthinkable for nearly any other act in the service of creating a memorable event that night. The Love Company, known for its installation work on Miami’s raging club scene, and painter Clifford Bailey came in to transform the Brutalist stadium concourse into a warm, inviting space. The towering concrete columns were draped in fabric. Photographs of Muddy Waters, Leadbelly, and other great American bluesmen—so inspirational to the band—were projected on giant screens overhead. Bailey’s canvases of musicians in ecstatic performance filled in the gaps. There was, naturally, the lips-and-tongue logo, carved in ice. The vast swamp of the Everglades could be seen spilling to the horizon, the absence of landmarks making the stadium feel almost like a ship at sea.

The Stones, often a spectral presence backstage, mingled with the crew and their families. Ronnie Wood and Keith Richards ambled through the dining area, garrulous and warm, patriarchs of this vagabond family. Wood, a noted painter in his own right, spent time watching Bailey complete a canvas of the band in action. After dinner, the crew worked diligently to make sure everything would be ready for the global audience of millions who would be watching the show the next night.

The band rehearsed “Live With Me” with Sheryl Crow, who was making the first of what would be many appearances with the legends. Bo Diddley romped through “Who Do You Love?” in defiance of the traditional post-Thanksgiving-dinner lassitude. A few of the crew’s children chased spotlight beams across the empty stadium field, while Mick and Keith, alone and acoustic, played “Wild Horses.”

For this traveling army, this night on the edge of the Everglades transcended the dislocation endemic to touring life. Full bellies, family, and a warm Florida night.

A person could dine out for a lifetime on stories gathered from an outing with any of these legends. There will, of course, be tales of exhaustion and exploration. Dig deeper, though, past the Domino’s, and you just might strike kedgeree.

Slightly too inspired by a Kiss concert he attended for his eighth birthday, Matthew Kronsberg went on to spend a decade in the concert industry, working with artists from Tony Bennett to U2. He is now a producer and writer living in Brooklyn, New York.